For some consumers, day one downloads have become a bit of a bugbear. Some feel like the use of it is a violation of trust between the consumer and the developer. You may have found yourself asking the question “I purchased this game, a finished product, so why do I need to wait for this download?” Or “Why are there game elements that were removed to sell me later?” As justified as these questions are, and as over used or misused as these practices may be, there are many very real, and very valid reasons for day one downloads. On top of that, there are other factors that add up to the current proliferation of this practice.

To start off, I want to point out that I will be talking about two distinct things here: the day one patch, and the day one DLC. Each of these has different aspects that may or may not make any given example a valid use case.

Origins: Development to Release as a strictly sequential process

Originally, the distribution of any home video game was as a boxed product. That means that whatever was in the box was what you got, no patches or upgrades or anything. This would also be independent of platform, so this applies to consoles, computers, or even arcade cabinets. Even updated versions would be rare, and only to address the most critical of issues, or a response to overwhelming success. Any other situation wouldn’t call for the additional cost of development, and certainly not the overwhelming cost of physical production and distribution. Development on the game was done, so now it’s time to sell it and to try to make the money back, not to spend more money on it. The only money you should be spending now should be producing inventory, advertising, and competing for shelf space at the games store. That’s quite enough cost as it is without adding to development costs. On top of that, consider that if you were to update a game, you would have needed to replace ALL OF THE COPIES that are out there. That would mean costs to notify the players, produce new inventory, and figure out how to distinguish the existing copies with the new ones, or if it’s a really bad problem, maybe recall copies still on the shelves.

What are all these zeroes? Wait, it costs HOW MUCH to patch a game!?

With that said, keep in mind that there are times where later versions of games have some bug fixes and tweaks, and often those were tweaks between production runs of the game and did not incur all of these other costs, since it was a quiet update, and no stock had to be replaced or recalled. These kinds of updates would only happen if the initial production run of the game was sold out, and there was clearly still demand to be satisfied. At that point, slight improvements to issues, either known ahead of time, or discovered after release, would not be disruptive to the production workflow. Engineers are still familiar with the code and could fit in a couple small improvements before the next batch is produced, essentially making a version 1.0.1, or whatever. That cost would be small compared to the oncoming expense of physical production and distribution, and could drive a few more sales, and/or show that as a developer you are working to make a better product and improve your standing among consumers.

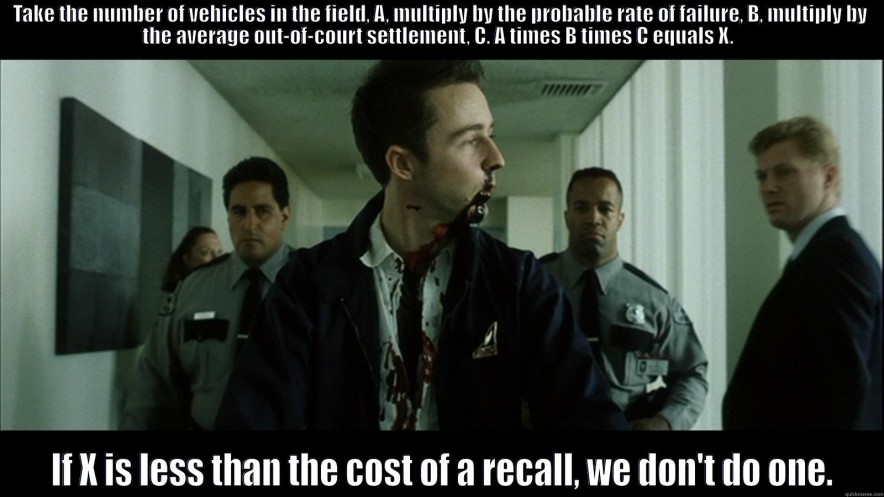

Gotta remember, this kind of calculation is actually important to keep people employed.

What Changed

You may have noticed how much I referenced the cost of the physical production and distribution so far. However, in the past decade or so, there has been a revolution in digital distribution. This unlocks nearly all of the cost concerns tied with physical goods. When software is no longer bound to physical media, there’s no longer the need for producing or distributing stock, or for fighting over shelf space at a store. Now with reliable and wide spread broadband as well as cheaper server space, companies can deliver updates, or even whole games, to a user at a small fraction of the cost from before. Now, not only is this cheaper, but it’s faster too. Currently, it can be possible to realize there’s an issue on a product, fix it, test it, and release it in an hour. That kind of response time obviously depends on a lot of other factors, but it is possible.

This is how the SaaS (software as a service) business model can work. With less cost associated with distributing new versions that money can go to continuing development, either fixing bugs or introducing new features. That continued support should then make the project more attractive to potential customers. From a business perspective, hopefully this is something that can justify a subscription fee. World of Warcraft aside, this doesn’t happen often in games these days, though. Instead, developers try to continue to support to try to increase the reach of the game to drive more sales, or even just improve the perception of the title and serve the players well.

What Hasn’t Changed

The software industry at large has been adapting to the implications of this, and the games industry in particular has been uniquely caught in between the old system and the new one. Games are unique because as an industry, it’s really somewhere between software, and movies, and that is where some of the friction comes in.

Often enough, movies live and die by their release date. If a movie is delayed, then all of the marketing machine that went into drumming up interest for the opening weekend is not only no longer fully valid, and even potentially counter productive. While games aren’t exactly the same, and the smaller the game is the less this applies, there is still a LOT of money and effort that goes into marketing, and a really big part of that is the release date. Having to change that can cause a lot of problems, and generate a lot of expense. Campaigns will have to be modified, or have their dates changed. But the dates of advertising campaigns aren’t arbitrary. They’re not all like digital distribution, where something can be started or stopped at any time. There are slots that fill up, so if you need to move it, you may not have any good dates left. There can also partners that expect something to be ready on a certain date. For example, even with digital distribution there are timed elements. Getting featured on a digital storefront is a HUGE opportunity, and one that a developer will rightly scramble and trip all over themselves to get secured. If you commit to that, and have to pull out, then the chances of getting that featured spot back could be permanently lost. All of this can add up to a loss of millions of dollars, which can easily break a product’s profitability.

Day one Patches

With all of this in mind, consider that the development teams will be working really hard to hit their release date. A lot of releases, even with digital distribution, and especially on consoles, there is a delay between when the developer hands off the build saying “This is ready to sell”, and when it shows up as available to the user. There are other requirements to be met, certifications to pass, and various other things that have to happen in between.

This can mean over a week of time between when the developer hands off the game, what is on disc when sold in stores, and when it is available to consumers. There can still be problems, sometimes really significant problems, with that version. However, developers are trying really hard to hit that date, since missing it is shooting the project in the foot, financially speaking. So, what are they to do when faced with problems that can’t be fixed in time? They can submit, and fix them in the time between that submission and when a consumer can play it. This is a gamble, and a balancing act. What are the consequences if the issues can’t be fixed in time? How much would it cost? Is it more than the cost of changing shipping dates, changing advertising, updating community events, and any of the other things that have to be considered?

There’s a less obvious side to the day one patch as well, for consoles at least. In the past, all games had to go through extensive certification at Sony/Microsoft/Nintendo before they would allow the game to be sold on their respective platforms. If it didn’t pass, you HAD to fix it. Now, however, it is easier to pass with issues on the premise that a patch will be made available. So, these requirements are no longer the absolute law that they used to be. Furthermore, while I don’t have any first hand knowledge of anything unscrupulous happening, I would not be surprised if money could allow that kind of exception to be handed out fairly easily.

Day one DLC

DLC is a different topic, but shares many similarities to day one patches with respect to the changes digital distribution has brought about.

First of all, we have had DLC around for a very long time, but we used to call it an “expansion”. The advent of digital distribution is what allowed DLC to become much easier to provide, and from that a more reliable option to increase the revenue of a game.

I say this as though packaged expansions aren’t still with us… More like this isn’t the ONLY option.

Now, I know what that can sound like. Some businessman looks at a game, sees it’s successful and thinks that slapping on some DLC is a way to squeeze more money out of players. Or, even worse, that cutting out a part of the game, only to sell it to players separately is how to manufacture DLC where none should apply. First of all I ask you to keep in mind that this really is a hit driven business, and most titles are inherently gambles. Even breaking even is asking quite a lot from a lot of games. If there is something that can be done to improve a game’s chances, many people would be highly tempted to take it. The game succeeding means the funding won’t dry up, and the developer won’t have to dissolve. These decisions can legitimately be made with the only concern being for keeping people working.

Anyhow, that’s about DLC in general. Day one DLC specifically has several things going on. First I will tackle this from the business side.

Consider this: demand is inherently going to be highest soon after the game is released. This is when the advertising and consumer interest will be at its peak. If DLC is available on the outset, it has the best chance of making the most sales possible. To illustrate this point, consider this. How many people would purchase an expansion to Sid Meyer’s “Pirates!” right now? It’s a good game, well liked, well remembered, so it would probably sell a handful of copies, but would that number be anywhere near what it would be if the same DLC were released 2 months after the game were released? It would absolutely not. So, what is the difference between DLC that is available the same day as the game, and months after the game is released? To the business side, sales.

On the development side, a different team of people from the main developer can produce DLC. So, if they are working on it and are done in time for release, there is nothing wrong with their product being put out alongside the main team’s product.

Really, though, no matter what the situation, if the expanded content is ready and available at the same time as the main game, there’s no harm in making it available to consumers right away. It’s actually a benefit to the players, as they don’t have to wait for any of these things. It would seem the main reason a consumer would complain is on the presumption that expanded material must inherently come later. That line of thinking is a false equivalence, though, brought about by the appearance of the digitally distributed DLC being “free”, in the sense that because there’s no physical copy, there’s no cost associated with providing it. Again, the only issue is the timing. DLC could be provided in a free update just as easily, but if it is a distinct product then it should be sold separately. The only way that this is an inherent sin against the consumer is if you were to argue against DLC in its entirety, and that’s a completely separate argument.

On Disc DLC

Finally, I want to touch on the idea of “on disc” DLC. This being something that is kept behind an additional DLC pay gate, but is in fact data that is included in the initial release, and therefore not distributed as a distinct product. This would likely be, but not necessarily limited to day one availability. This is something that I can still see a legitimate application for, but is easily a much darker shade of gray. I can see two ways that this is ethically viable.

First, the content was intended to be DLC, but some assets were able to fit in the initial release. The DLC patch that is needed to activate this also includes code to actually make other things work. Essentially, most of the content is there, but it is not in a functional state “on disc”, and additional work is needed to make it work. This makes sense, if you think about it, in the sense that any DLC would have to have some hooks in the main game to allow it to work with different or expanded content. How I just described “on disc” DLC would be the same thing, just with the divider farther out, with things like art assets included, but the working bits like game tuning or AI not included yet.

Second, this is intended to be a separate product, and does not impact the core experience, and there is a performance impact if it is not included in the main game. Street Fighter costume packs are a good example of this. If you have a match with someone else online who has a purchased costume, you HAVE to have that asset on your game to be able to see it. This can be distributed by a version update, meaning everyone has the assets in their local copies of the game already, even if they aren’t explicitly on the disc. So consider a later printing of the game. When this is done, it would be preferable if they print on the disc a later version of the game so that it can be played with less updating on start up. With this, bug fixes and costume packs will be included because it’s the updated version. You have it on disc, are you therefore entitled to have those costume packs at no additional charge? No, you have the exact same access, and the same product, as everyone else.

To be fair, it’s Capcom. They’re laughing especially hard because someone asked them when they’ll make another MegaMan game.

Final Thoughts

I want to stress that, while I’ve argued for valid applications of day one downloads, I am not saying that they can’t be abused. As I explained, day one patches can be used as an excuse to shove poor products through certification. I also want to stress that what I’ve said on DLC is assuming that the DLC in question is NOT a case of core content being withheld to artificially create an additional pay gate that players must pass through for the full experience. That particular practice would have to be judged on a case by case basis.

I am not saying that there are not developers or producers that would do such a thing. I am simply trying to shine a light on legitimate applications for these practices, what makes them legitimate, and why they would be implemented.

Kynetyk is a veteran of the games industry. Behind the Line is written to help improve understanding of what goes on in the game development process and the business behind it. From “What’s taking this games so long to release”, to “why are there bugs”, to “Why is this free to play” or anything else, if there is a topic that you would like to see covered, please write in to kynetyk@enthusiacs.com

![[PROTOTYPE]](http://www.enthusiacs.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/title-104x104.jpg)

Behind the Line: Day one downloads

For some consumers, day one downloads have become a bit of a bugbear. Some feel like the use of it is a violation of trust between the consumer and the developer. You may have found yourself asking the question “I purchased this game, a finished product, so why do I need to wait for this download?” Or “Why are there game elements that were removed to sell me later?” As justified as these questions are, and as over used or misused as these practices may be, there are many very real, and very valid reasons for day one downloads. On top of that, there are other factors that add up to the current proliferation of this practice.

To start off, I want to point out that I will be talking about two distinct things here: the day one patch, and the day one DLC. Each of these has different aspects that may or may not make any given example a valid use case.

Origins: Development to Release as a strictly sequential process

Originally, the distribution of any home video game was as a boxed product. That means that whatever was in the box was what you got, no patches or upgrades or anything. This would also be independent of platform, so this applies to consoles, computers, or even arcade cabinets. Even updated versions would be rare, and only to address the most critical of issues, or a response to overwhelming success. Any other situation wouldn’t call for the additional cost of development, and certainly not the overwhelming cost of physical production and distribution. Development on the game was done, so now it’s time to sell it and to try to make the money back, not to spend more money on it. The only money you should be spending now should be producing inventory, advertising, and competing for shelf space at the games store. That’s quite enough cost as it is without adding to development costs. On top of that, consider that if you were to update a game, you would have needed to replace ALL OF THE COPIES that are out there. That would mean costs to notify the players, produce new inventory, and figure out how to distinguish the existing copies with the new ones, or if it’s a really bad problem, maybe recall copies still on the shelves.

What are all these zeroes? Wait, it costs HOW MUCH to patch a game!?

With that said, keep in mind that there are times where later versions of games have some bug fixes and tweaks, and often those were tweaks between production runs of the game and did not incur all of these other costs, since it was a quiet update, and no stock had to be replaced or recalled. These kinds of updates would only happen if the initial production run of the game was sold out, and there was clearly still demand to be satisfied. At that point, slight improvements to issues, either known ahead of time, or discovered after release, would not be disruptive to the production workflow. Engineers are still familiar with the code and could fit in a couple small improvements before the next batch is produced, essentially making a version 1.0.1, or whatever. That cost would be small compared to the oncoming expense of physical production and distribution, and could drive a few more sales, and/or show that as a developer you are working to make a better product and improve your standing among consumers.

Gotta remember, this kind of calculation is actually important to keep people employed.

What Changed

You may have noticed how much I referenced the cost of the physical production and distribution so far. However, in the past decade or so, there has been a revolution in digital distribution. This unlocks nearly all of the cost concerns tied with physical goods. When software is no longer bound to physical media, there’s no longer the need for producing or distributing stock, or for fighting over shelf space at a store. Now with reliable and wide spread broadband as well as cheaper server space, companies can deliver updates, or even whole games, to a user at a small fraction of the cost from before. Now, not only is this cheaper, but it’s faster too. Currently, it can be possible to realize there’s an issue on a product, fix it, test it, and release it in an hour. That kind of response time obviously depends on a lot of other factors, but it is possible.

This is how the SaaS (software as a service) business model can work. With less cost associated with distributing new versions that money can go to continuing development, either fixing bugs or introducing new features. That continued support should then make the project more attractive to potential customers. From a business perspective, hopefully this is something that can justify a subscription fee. World of Warcraft aside, this doesn’t happen often in games these days, though. Instead, developers try to continue to support to try to increase the reach of the game to drive more sales, or even just improve the perception of the title and serve the players well.

What Hasn’t Changed

The software industry at large has been adapting to the implications of this, and the games industry in particular has been uniquely caught in between the old system and the new one. Games are unique because as an industry, it’s really somewhere between software, and movies, and that is where some of the friction comes in.

Often enough, movies live and die by their release date. If a movie is delayed, then all of the marketing machine that went into drumming up interest for the opening weekend is not only no longer fully valid, and even potentially counter productive. While games aren’t exactly the same, and the smaller the game is the less this applies, there is still a LOT of money and effort that goes into marketing, and a really big part of that is the release date. Having to change that can cause a lot of problems, and generate a lot of expense. Campaigns will have to be modified, or have their dates changed. But the dates of advertising campaigns aren’t arbitrary. They’re not all like digital distribution, where something can be started or stopped at any time. There are slots that fill up, so if you need to move it, you may not have any good dates left. There can also partners that expect something to be ready on a certain date. For example, even with digital distribution there are timed elements. Getting featured on a digital storefront is a HUGE opportunity, and one that a developer will rightly scramble and trip all over themselves to get secured. If you commit to that, and have to pull out, then the chances of getting that featured spot back could be permanently lost. All of this can add up to a loss of millions of dollars, which can easily break a product’s profitability.

Day one Patches

With all of this in mind, consider that the development teams will be working really hard to hit their release date. A lot of releases, even with digital distribution, and especially on consoles, there is a delay between when the developer hands off the build saying “This is ready to sell”, and when it shows up as available to the user. There are other requirements to be met, certifications to pass, and various other things that have to happen in between.

This can mean over a week of time between when the developer hands off the game, what is on disc when sold in stores, and when it is available to consumers. There can still be problems, sometimes really significant problems, with that version. However, developers are trying really hard to hit that date, since missing it is shooting the project in the foot, financially speaking. So, what are they to do when faced with problems that can’t be fixed in time? They can submit, and fix them in the time between that submission and when a consumer can play it. This is a gamble, and a balancing act. What are the consequences if the issues can’t be fixed in time? How much would it cost? Is it more than the cost of changing shipping dates, changing advertising, updating community events, and any of the other things that have to be considered?

There’s a less obvious side to the day one patch as well, for consoles at least. In the past, all games had to go through extensive certification at Sony/Microsoft/Nintendo before they would allow the game to be sold on their respective platforms. If it didn’t pass, you HAD to fix it. Now, however, it is easier to pass with issues on the premise that a patch will be made available. So, these requirements are no longer the absolute law that they used to be. Furthermore, while I don’t have any first hand knowledge of anything unscrupulous happening, I would not be surprised if money could allow that kind of exception to be handed out fairly easily.

Day one DLC

DLC is a different topic, but shares many similarities to day one patches with respect to the changes digital distribution has brought about.

First of all, we have had DLC around for a very long time, but we used to call it an “expansion”. The advent of digital distribution is what allowed DLC to become much easier to provide, and from that a more reliable option to increase the revenue of a game.

I say this as though packaged expansions aren’t still with us… More like this isn’t the ONLY option.

Now, I know what that can sound like. Some businessman looks at a game, sees it’s successful and thinks that slapping on some DLC is a way to squeeze more money out of players. Or, even worse, that cutting out a part of the game, only to sell it to players separately is how to manufacture DLC where none should apply. First of all I ask you to keep in mind that this really is a hit driven business, and most titles are inherently gambles. Even breaking even is asking quite a lot from a lot of games. If there is something that can be done to improve a game’s chances, many people would be highly tempted to take it. The game succeeding means the funding won’t dry up, and the developer won’t have to dissolve. These decisions can legitimately be made with the only concern being for keeping people working.

Anyhow, that’s about DLC in general. Day one DLC specifically has several things going on. First I will tackle this from the business side.

Consider this: demand is inherently going to be highest soon after the game is released. This is when the advertising and consumer interest will be at its peak. If DLC is available on the outset, it has the best chance of making the most sales possible. To illustrate this point, consider this. How many people would purchase an expansion to Sid Meyer’s “Pirates!” right now? It’s a good game, well liked, well remembered, so it would probably sell a handful of copies, but would that number be anywhere near what it would be if the same DLC were released 2 months after the game were released? It would absolutely not. So, what is the difference between DLC that is available the same day as the game, and months after the game is released? To the business side, sales.

On the development side, a different team of people from the main developer can produce DLC. So, if they are working on it and are done in time for release, there is nothing wrong with their product being put out alongside the main team’s product.

Really, though, no matter what the situation, if the expanded content is ready and available at the same time as the main game, there’s no harm in making it available to consumers right away. It’s actually a benefit to the players, as they don’t have to wait for any of these things. It would seem the main reason a consumer would complain is on the presumption that expanded material must inherently come later. That line of thinking is a false equivalence, though, brought about by the appearance of the digitally distributed DLC being “free”, in the sense that because there’s no physical copy, there’s no cost associated with providing it. Again, the only issue is the timing. DLC could be provided in a free update just as easily, but if it is a distinct product then it should be sold separately. The only way that this is an inherent sin against the consumer is if you were to argue against DLC in its entirety, and that’s a completely separate argument.

On Disc DLC

Finally, I want to touch on the idea of “on disc” DLC. This being something that is kept behind an additional DLC pay gate, but is in fact data that is included in the initial release, and therefore not distributed as a distinct product. This would likely be, but not necessarily limited to day one availability. This is something that I can still see a legitimate application for, but is easily a much darker shade of gray. I can see two ways that this is ethically viable.

First, the content was intended to be DLC, but some assets were able to fit in the initial release. The DLC patch that is needed to activate this also includes code to actually make other things work. Essentially, most of the content is there, but it is not in a functional state “on disc”, and additional work is needed to make it work. This makes sense, if you think about it, in the sense that any DLC would have to have some hooks in the main game to allow it to work with different or expanded content. How I just described “on disc” DLC would be the same thing, just with the divider farther out, with things like art assets included, but the working bits like game tuning or AI not included yet.

Second, this is intended to be a separate product, and does not impact the core experience, and there is a performance impact if it is not included in the main game. Street Fighter costume packs are a good example of this. If you have a match with someone else online who has a purchased costume, you HAVE to have that asset on your game to be able to see it. This can be distributed by a version update, meaning everyone has the assets in their local copies of the game already, even if they aren’t explicitly on the disc. So consider a later printing of the game. When this is done, it would be preferable if they print on the disc a later version of the game so that it can be played with less updating on start up. With this, bug fixes and costume packs will be included because it’s the updated version. You have it on disc, are you therefore entitled to have those costume packs at no additional charge? No, you have the exact same access, and the same product, as everyone else.

To be fair, it’s Capcom. They’re laughing especially hard because someone asked them when they’ll make another MegaMan game.

Final Thoughts

I want to stress that, while I’ve argued for valid applications of day one downloads, I am not saying that they can’t be abused. As I explained, day one patches can be used as an excuse to shove poor products through certification. I also want to stress that what I’ve said on DLC is assuming that the DLC in question is NOT a case of core content being withheld to artificially create an additional pay gate that players must pass through for the full experience. That particular practice would have to be judged on a case by case basis.

I am not saying that there are not developers or producers that would do such a thing. I am simply trying to shine a light on legitimate applications for these practices, what makes them legitimate, and why they would be implemented.

Kynetyk is a veteran of the games industry. Behind the Line is written to help improve understanding of what goes on in the game development process and the business behind it. From “What’s taking this games so long to release”, to “why are there bugs”, to “Why is this free to play” or anything else, if there is a topic that you would like to see covered, please write in to kynetyk@enthusiacs.com