The Big Book Of Controversies – Chapter II

Nintendo v. Sony

1991

As early as 1986, Nintendo had been toying with the idea of introducing disc-based technologies into their consoles. But with the current hardware available to them, these rewritable magnetic discs could be easily wiped out and erased, coupled with the fact that these discs lacked any sort of copy protection, and were easy prey to piracy.

With the emergence of the CDROM/XA programming in early 1991, Nintendo’s interest was piqued. Simultaneously developed by Sony and Philips, CD-ROM/XA is an extension of the CD-ROM format that combines compressed audio, visual, and computer data that allows all to be accessed simultaneously and, at the time, made it extremely difficult to pirate. Nintendo initially began to work with Sony to develop a CD-ROM add-on for their current 16-bit Super Nintendo and Super Famicom consoles. A contract was eventually brokered, and work began on the prototype.

By May of 1991, The “SNES-CD” was ready to go, and was set to be announced at the upcoming Consumer Electronics Show. However, when Nintendo’s then-President Hiroshi Yamauchi read the original 1988 contract between Sony and Nintendo, he realized that this agreement essentially handed Sony almost complete and total control over any and all of Nintendo’s titles written on the SNES-CD format. Furious, Yamauchi decided that the contract was totally unacceptable and secretly canceled all plans for the Nintendo-Sony SNES CD attachment.

Instead of announcing the partnership between Sony and Nintendo at 9 a.m. on the day of their C.E.S. presentation, Nintendo chairman Howard Lincoln instead stepped onstage and revealed that Nintendo had allied with Philips, and that Nintendo was abandoning all previous work Nintendo and Sony had, up until then, accomplished. You see, not long after Nintendo’s private about-face, Lincoln and then current president of Nintendo of America, Minoru Arakawa, had flown to Philips headquarters in Europe prior to the public announcement and had formed a new and decidedly different partnership – one that would give Nintendo complete and total control over its licenses on Philips machines.

After their partnership fell through with Nintendo, Sony considered halting their research, but ultimately decided to use what they had developed thus far and remake it into a complete, stand-alone console. When Nintendo caught wind of this decision, it filed a lawsuit claiming breach of contract and attempted, in U.S. federal court, to obtain an injunction against the release of this “Play Station” device on the grounds that Nintendo (theoretically) somehow still owned the name. The case ultimately denied Nintendo’s injunction and, in October 1991, the first hint of this new “Play Station” was revealed.

By the end of 1992, Sony and Nintendo once again attempted a (by some accounts, one-sided) new partnership deal, whereby the Play Station would still have a port for SNES cartridges, but Nintendo would maintain the rights and receive the bulk profits from the games, and the SNES would continue to use the Sony-designed audio chip.

However, dissatisfied with this set-up, Sony decided in early 1993 to rework the Play Station to target a new generation of hardware and software. The SNES cart port was dropped and the space between the names “Play Station” was removed, renaming itself “PlayStation”. With this last step taken, Nintendo’s involvement in Sony’s new CD driven console was all but done and done, and Sony’s first steps into the video game landscape would soon change the very way we play and interact with games as a whole.

Video Game Violence And The Manhunt Against Manhunt

1990’s – current

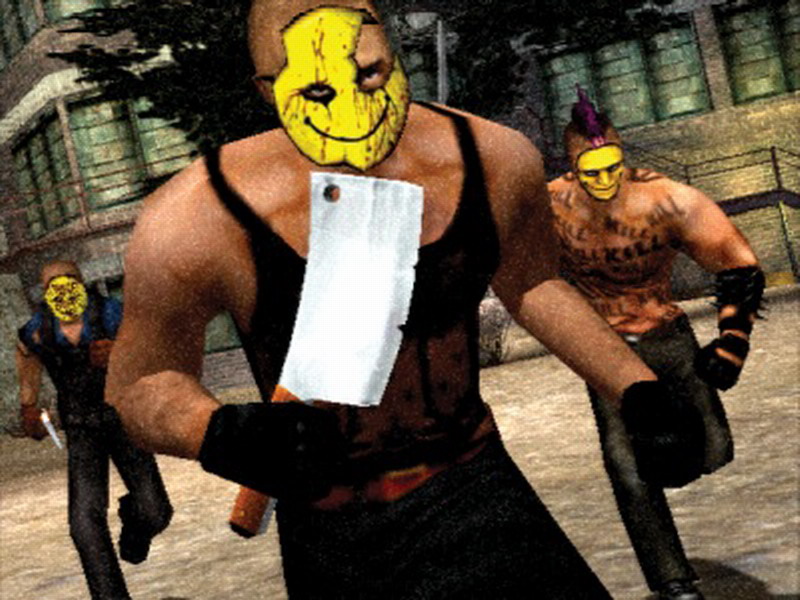

By 1990, as video game interactivity started reaching more realistic depths, the dispute on a social and scientific level began to imply that video game consumption could have a negative impact on the human psyche, both on a conscious and subconscious level. The more violent the video game, some theorists contended, the more violent and anti-social a person becomes. Many argued that, as video games matured and became more realistic in their approach (and depictions) towards violence, the more negative or “desensitized” a person becomes towards real-world atrocities. Some even argue that violent video games are the root cause for some of the most horrendous incidences in American society in recent years. Controversies surrounding such games as Manhunt for example are used as prime examples of why, in their opinion, the video game industry must be regulated on a governmental level.

U.S. Representative Joe Baca even cited Manhunt as one of the reasons to sponsor legislation to fine those who sell adult-themed games to players younger than 17. Baca said of the game that “it’s telling kids how to kill someone, and it uses vicious, sadistic and cruel methods to kill.” But it wasn’t until July 28 of 2004 that the title received world-wide attention when the game was linked to the murder of 14-year-old Stefan Pakeerah by his 17-year-old friend Warren Leblanc in Leicestershire, England. Initially, the media reports indicated that police had found a copy of the game in Leblanc’s bedroom, and that the victim’s mother, Giselle Pakeerah stated that Warrnen “… was obsessed by this game. To quote from the website that promotes it, it calls it a psychological experience, not a game, and it encourages brutal killing. If he was obsessed by it, it could well be that the boundaries for him became quite hazy.”

During the subsequent consumer outrage, the game was removed from shelves by some vendors, including both the UK and international branches of video game retailers Game and Dixons Retail, one of the largest consumer electronics retailers in Europe. Following the murder, U.S. attorney Jack Thompson a strong opponent of violence in video games and the culture of video gaming in general, claimed that he had written to Manhunt’s developer, Rockstar, warning them that the nature of the game could inspire “real world” copycat killings. “I wrote [Rockstar] warning them that somebody was going to copy the game and kill somebody. We have had dozens of killings in the U.S. by children who had played these types of games. This is not an isolated incident. These types of games are basically murder simulators. There are people being killed over here almost on a daily basis.”

Thompson was subsequently hired by the Pakeerah family with the intent of suing both Rockstar and Sony Computer Entertainment in a £50 million wrongful death claim. However, on the same day that Thompson had been hired by the family, the local Leicestershire Constabulary came forward to state that the initial media reports were wrong. “The video game was not found in Warren LeBlanc’s room, it was found in Stefan Pakeerah’s room. Leicestershire Constabulary stands by its response that police investigations did not uncover any connections to the video game…..” The Constabulary went on to say that the incident was instead a drug-related robbery and revealed that the game had absolutely no link to the subsequent murder.

The Pakeerah’s case against Sony and Rockstar was dropped soon thereafter. But the argument of the negative impact of violent content in video games still rages on.

The Console Wars: Part II – The Notorious “Saturnday” Incident

1995 – 1998

As 1994 drew to a close, and as the era of a the 16-bit generation was reaching its final days here in North America, the gaming community was eagerly anticipating a new 32-bit machine monster released earlier in Japan. In 1995, Sega president Tom Kalinske announced that this new “Sega Saturn” would launch in the U.S. on “Saturnday”, September 2, 1995. However, on May 11, 1995, at the first Electronic Entertainment Expo, Kalinske announced that this “Saturnday” date was a trick and that the system was being released immediately at a full 4 months ahead of schedule.

This “surprise attack” backfired on Sega for several reasons. First, The Saturn’s high price point of $399 let Sony announce a $299 price for the PlayStation as a response. Second, This too-early launch also meant that the Saturn had only 6 games available for it, since most of Sega’s third-party games were still slated to be completed by the original September launch date.

Third, many of Sega’s third-party publishers, particularly those based in North America, were angered at the surprise announcement since many of their own titles were far from completed. Essentially the only games available on the shelves at launch would be software made and released by Sega. Rumors would later suggest that this incident was a calculated move on Sega’s part to garner larger sales of their own software at the expense of their independent developers.

Fourth, and possibly the most damaging of all for the Sega Saturn’s future, several retailers who were not included in the early launch program, notably Wal-Mart and KB Toys, became outright hostile towards Sega of America. Some retailers aggressively and openly supported Sega’s rivals, causing Sega to have difficulties with distributors for a very significant period of time. In fact, Sega’s actions angered KB Toys alone so much that they refused to release the Saturn at all, and actually went as far as having their distributors remove anything Sega-related to provide more retail space for the Saturn’s competition. By the time of the PlayStation’s U.S. release on September 9, 1995, the Saturn had sold approximately 80,000 systems in North America. For all intents and purposes, the Sega Saturn was a flop, and caused Sega to lose an estimated $267.9 million in revenue which forced them to lay off roughly 30% of its workforce.

The PlayStation, on the other hand, enjoyed a rather successful launch with quite a few successful titles including the Battle Arena Toshinden, Doom, Warhawk, Air Combat, Philosoma, and Ridge Racer titles. It should also be noted that, in addition to playing games, the PlayStation was one of the first consoles that had the ability to read and play audio CDs and was the first home console unit to utilize separate memory cards to save in-game progress.

Perhaps the biggest coup to occur in Sony’s favor was the exclusive release of Square’s (Now Square-Enix) blockbuster Final Fantasy VII. Originally, FF VII was to be released for the SNES, but was eventually pushed back as a release title for the upcoming Nintendo 64. However, with the limitations of data storage on cart based games, coupled with the fact that games were becoming considerably more complex (in story content, graphical enhancements and sound), not to mention that the cost of production was considerably more cheaper, Sony had effectively demonstrated the viability and flexibility of CD-based gaming. Many big name third-party developers began to give Sony weight as it entered the market in force. And, by the end of its near 11-year run, The PlayStation had become the first home gaming console to top over 100 million units sold.

With the new hardware releases from Sega and PlayStation, Nintendo decided to finally throw its hat back into the ring. With the SNES no longer a viable competitor in the marketplace, a new console design began to take form. Dubbed “Project Reality”, Nintendo’s new entry into the console wars went underway. However, Project Reality faced several roadblocks while being developed. One of which was Nintendo’s refusal to adopt the CD-ROM format, instead opting to retain the cartridges that had been proven to be limiting in storage space, graphical punch, and sound. This in turn left many third-party developers feeling cold. Many of them began jumping ship, opting to try their hand with the more successful and more mature rated PlayStation. Also, because of the carts, the smaller storage size limited the number of textures, resulting in many games that had blurry graphics, low-resolution textures, and what became known as “distance fogging.”

Despite all of this, Nintendo pushed ahead with their new 64-bit unit, and was first unveiled in playable form to the public on November 24, 1995 at the 7th Annual Shoshinkai Software Exhibition in Japan with the tagline of “Get N or Get Out!” Officially released in Japan June 23, 1996, followed by a North American release on September 29, 1996 and in Europe on March 1, 1997, the N64 managed to sell 500,000 units in the first four months of release and enjoyed a fairly well received life. All told, however, Japanese sales were significantly less than what had been anticipated. Later day speculation suggested that the N64’s lower popularity in Japan was due to the lack of a robust role-playing games library. In fact during its lifespan, only 6 out of the total 386 games released for the N64 were actually considered RPG’s. And of those, only two were exclusively available in Japan.

It should be noted, however, that the N64 is remembered mostly by several high-profile and highly successful game titles. Among these were the original GoldenEye 007, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Perfect Dark, and some of the early Turok titles. GoldenEye 007 itself is still remembered by many as the singular best FPS game for its time, with The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina being regarded as the N64’s best story driven game of the last decade.

Pages: 1 2

Man…do new consoles EVER have good launch libraries anymore? It seems like if you’re not waiting at least 2 years after launch the pickings are going to be slim these days.

And to think-had there plan gone together, Sony might of not been the media giant it is today (I mean video games, of course Sony is a media giant just not in that way)