The Big Book of Controversies: Chapter I

Controversy: n. plural: controversies – 1. a prolonged public dispute, debate, or contention; disputation concerning a matter of opinion. 2. contention, strife, or argument.

My Fellow Gamers;

When you look back deep into the heart of video gaming, you can see a litany of questionable intent. Questionable motivations. Questionable ethical and moral choices. What started out as a simple form of entertainment, for children no less, has lost itself in its own political machinations. As once-thought noble endeavors slowly turned into corporate ambitions, an innocence has been irrevocably lost along the way. Instead of simply being a form of escapist fun, now we have commentary on the societal culture that it has forged. Now we face the thought of how Mario, once simply the hero on a quest to rescue the Princess from the evil intent of the reptilian king Bowser; now we have dissertations into the Tropes of female roles in video games being nothing more than reward items for the male power fantasy.

Instead of celebrating the accomplishments of female lead roles in the likes of Samus and Lara Croft, now we have opinion pieces dissecting how they are nothing more than objectifying the sexual inequality in gaming. Instead of simply enjoying the exploits of tough, but still likeable, male and female characters, we have cries of misogyny simply for the sake of misogyny. The GamerGate conundrum is, however, simply one of many arguments that have bound itself to the tapestry of the video game subculture. To truly see where it all began, and what kind of legacy the current cultural crisis has been forged from, well, you have to travel back into the past, to see what kind of future is being currently written before us.

Please note that, though I have tried to keep the timeline as close as possible, some entries may be slightly out of chronological order. Though I have tried to keep the various events as close to each other as possible (within a span of a decade or less), I have missed many simply because information is difficult to keep track of when you’re going by memory. I do apologize for this, but I also hope that the following events give you a deeper understanding of where we are today, and why the video game culture is the way it is now. With that said, let’s begin shall we?

Atari/Kee Games

1973 – 1978

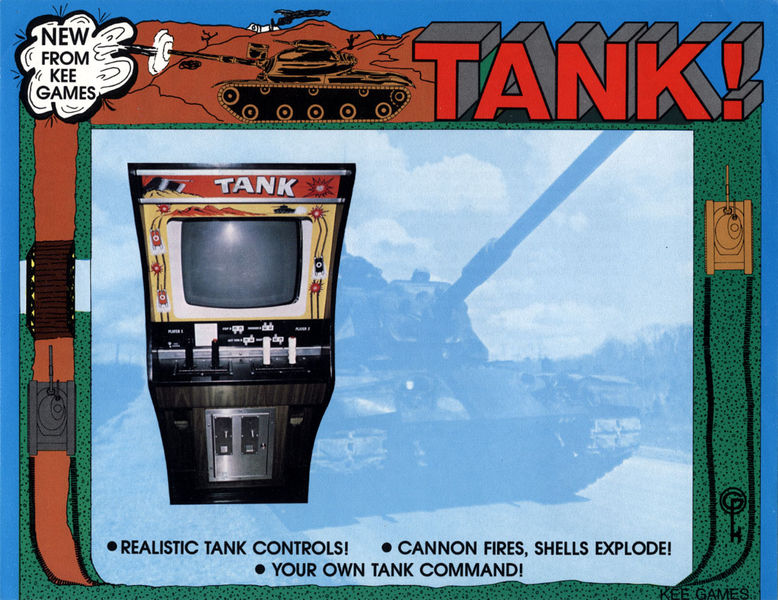

In the early years of Atari games, co-founders Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney were finding out the hard way that potential distribution partners didn’t want to be secondary distributors to secondary release titles. To drum up interest in “exclusive releases” to various companies, Bushnell hired long time friend (and next door neighbor) Joe Keenan to form rival gaming company Kee Games in an effort to circumvent arcade exclusivity deals with major outlets, thereby allowing both Atari and Kee Games to market quite literally the same type of game to two separate distributors with each company getting “exclusive deals” on the game.

Kee’s relationship to Atari was discovered a year later; however, Keenan had done such a tremendous job at managing the subsidiary that he was later promoted to President of Atari later that year, with Bushnell choosing to focus on the engineering aspects of the company. The incident in question may not have raised many eyebrows at the time, but you can begin to see the less than truthful intentions, and the less than honest formations, of the video gaming mentality.

North American Video Game “Crash” of 1983

1983

The early ’80’s would be a bad time for video games. A plethora of would-be (and even public knock-off versions of) Atari competitors had not only entered the marketplace, but a number of seriously mismanaged decisions would all but effectively shut down the industry.

By 1982, the market had become over-saturated by console contenders; The Atari 2600, The Atari 5200, Bally Astrocade, ColecoVision, Coleco Gemini, Emerson Arcadia 2001, Fairchild Channel F System II, Magnavox Odyssey2, The Intellivision, Intellivision 2, Sears Tele-Games, The TandyVisioN, The Vectrex, even Quaker Oats was trying to open up its own game division; though this was ultimately more to impress the stockholders than it was in gearing up for any kind of console platform.

Contributing to the crash were several other factors, such as the aggressive push for attention between console and PC gaming, with PCs generally promising more memory and faster processors over consoles. Other factors, such as loss of publishing control, hit Atari the hardest. Rival publishing house Activision was formed primarily due to the fact that Atari did not allow credits to appear on the games and did not pay employees a royalty based on sales. This schism eventually lead to pricey court battles that Atari eventually lost. With the loss of quality hardware programmers, all rushing to cash in on the video game boon at the time, this eventually lead to poorly constructed, and poorly received, games that further damaged the industry’s credibility and viability.

However, if one were to look at the main core contributing factors for the Crash of ’83, two of Atari’s game releases were ultimately cited as being responsible. In 1982, Atari attempted to cash in on the arcade popularity of Namco’s now-famous Pac-Man. Initially, Atari believed the conversion would be fairly simple because the arcade’s success was attributed to the gameplay rather than its visuals. Atari programmer Tod Frye completed the initial, and so far the only known version of, the Atari port in a mere 6 weeks. By March of 1982, the game was ready for sale.

However, Atari would make several critical missteps in their marketing of the game. For one, Atari overestimated demand, instead opting to green-light production of 12 million units, anticipating sales to easily reach well over $500,000,000 in returns. What came after was not what they expected. This meant that as stores tried to return the surplus games to the new publishers, the publishers had neither new products nor cash to issue refunds to the retailers.

So while Pac-Man went on to sell over 2 million units, by the summer of 1982 sales had unfortunately, and quite abruptly, slowed. Critical response was universally negative, and customer returns had pushed unsold copies to over 5 million units still sitting on store shelves. With the subsequent release of Atari’s next major release, E.T., during the Christmas holiday buying season of the same year failing to recapture the market and renew consumer confidence in the company, the video game home console had all but effectively been shut down.

Many of the console makers were eventually forced to close down their video game divisions (or close down completely), citing massive losses of revenue amid record levels of retail skepticism and mistrust. By 1983, Atari was merely a shell of its former self, having reported losses in excess of $300 million, with its workforce cut by over 30%. With millions of unsold copies of both Pac-Man and E.T., as well as hundreds of thousands of console boxes no one wanted just sitting in their warehouses, Atari did the only thing they knew to do, they buried their dead in a New Mexico landfill.

Atari’s Burial Ground

1983

On September 26, 1983, The Alamogordo Daily New began a series of reports stating that over 10 to 20 semi-trailer trucks were unloading large boxes of unsold cartridges, defunct computer systems, and unsold Atari console systems into the Alamogordo, New Mexico landfill, with the cartridges crushed and eventually buried under a thick layer of concrete. It became so commonplace in the city that the residents began to protest, with the city’s then Mayor, Henry Pacelli stating, “We don’t want to be an industrial waste dump for Atari. We don’t want to see something like this happen again.” The city eventually passed an Emergency Management Act and created the Emergency Management Task Force to limit the future flexibility of garbage contractors to secure outside businesses for the landfill for monetary purposes.

For over three decades, Atari refused to comment or even acknowledge the incident had occurred or was as bad as publicly perceived; instead opting for various pundits to layer on an aura of urban legend. But on April 26, 2014, online interactive and marketing agency Fuel Industries (along with Microsoft Corp.) was granted access to excavate the landfill as part of the 30th anniversary documentary detailing the incident. The excavators quickly revealed the existence of not only the unsold ET games, but also console hardware, computer systems and various other titles that affirmed the original speculation on the landfill’s contents. Roughly 1,300 games were recovered during the company’s limited time at the landfill, with many given for curation while the rest were auctioned off to raise money for a museum to commemorate the burial.

For nearly two years, the gaming landscape had been stripped bare with many, if not all, of the gaming focus put towards the superior marketability of home computers. “PC gaming” had reached a record boon, with early computer systems, such as the Commodore 64, receiving the lion’s share of gamers’ attentions. Text adventures and interactive fiction programs bootstrapped together from “Bedroom Coders” (as they were eventually called) gave rise to instant classics such as The Bard’s Tale, Pool of Radiance, Zork!, and Lode Runner (to name a few), and helped to secure financial stability for a number of developers and publishers still active today. Most notably among them would be Electronic Arts.

It wasn’t until a still relatively unheard of Japanese developer arrived in the states in the summer of 1985 that renewed interest in the home console market began to take off.

That company’s name was Nintendo.

Atari vs. Nintendo

1986 – 1992

Following a successful run producing arcade classics such as Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr., and Popeye, Nintendo began early work on a gaming console device for the Japanese market. This Family Computer, or the “Famicom,” hit some initial bad design bumps before being reworked and re-released to the public. But by the end of 1984 the Famicom had become the fastest and best selling game console in Japan.

Encouraged by their success, Nintendo soon began to turn their attention to the overseas marketplace. Initially, Nintendo opened negotiations with Atari with the intent that Nintendo would release the Famicom under Atari’s name as the Nintendo Advanced Video Game System. However that initial deal fell through after Atari executives discovered that Nintendo had released a port of Donkey Kong on the ColecoVision, which had been one of Atari’s main competitors before the crash occurred.

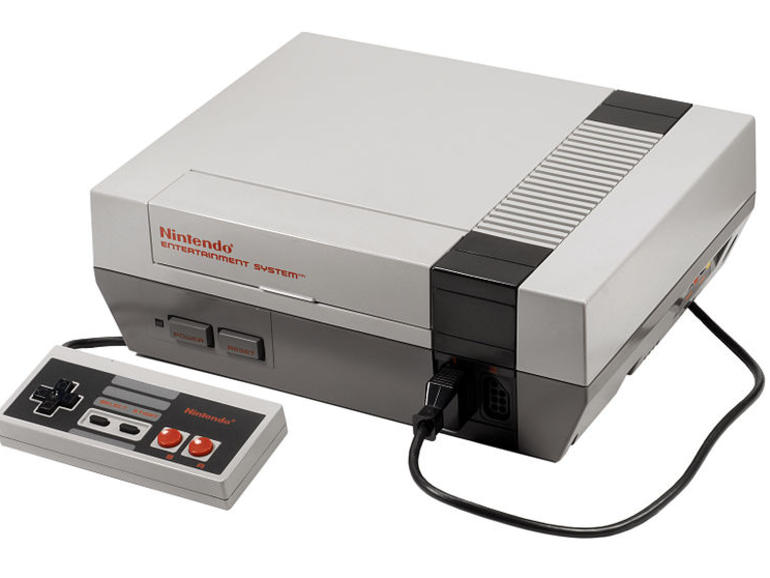

Undaunted, Nintendo decided to press on and, at the June 1985 Consumer Electronics Show, unveiled their new “Nintendo Entertainment System” to limited markets beginning in New York, with the promise of a full-on North American release by February of 1986. During that time, Nintendo began readying 18 separate launch titles, most notably of which were the ExciteBike, Duck Hunt, Wild Gunman, and Super Mario Bros. titles.

And this is where things get extremely rocky between Atari and Nintendo. By December of 1987, Atari had become a licensee of Nintendo, gaining the rights to make video games for the NES. The terms allowed Nintendo strict control to the console’s technology, namely to the company’s “10NES” lockout system that prevented illegal or unauthorized games from playing on the console. Atari was required to give their various game titles to Nintendo, who would then place the game on cartridges, install the 10NES system with it, and then resell the finished product to Atari.

In 1988, Atari illegally obtained the source code for the 10NES after alleging that a copy of the code was needed in a copyright infringement lawsuit. Atari then used the code to develop its own version of the 10NES, the Rabbit, which generated signals functionally indistinguishable from the 10NES. When Nintendo caught wind of this, they sued Atari, alleging fraud and infringement of its copyright. Atari counter-sued, alleging copyright misuse.

On September 10, 1992, the courts found that Atari had indeed infringed on Nintendo’s copyright by creating verbatim and substantially similar copies of the protected elements of the 10NES chip, and had done so fraudulently. Atari was also unsuccessful in claiming that such copying was fair use, or that Nintendo had misused its copyright.

The “Console Wars” Begin

1986 – Current

In 1986, from humble beginnings as an amusement park coin-operated slot machine and jukebox distributor to innovative arcade gaming designer, SEGA began to eye Nintendo’s American pie. Less than a year after Nintendo had entered the marketplace Sega, in conjunction with Tonka Toys, released their Master System as a direct competitor to Nintendo’s near dominance of the market. Technically superior to Nintendo’s current hardware, the Master System unfortunately didn’t catch on. Having learned lessons on the market a year prior, Nintendo employed highly aggressive marketing strategies to quell Sega’s uprising. Coupled with this, and by poor and ineffective marketing campaigns on Tonka’s part, Nintendo all but killed the Master System’s chance in North America.

It should be noted, however, that in overseas and South American markets, namely Brazil, Sega’s Master System literally trounced Nintendo. In fact it was such a huge hit in Brazil alone that Sega continued to produce and market the system there all the way up to 2000, with emulator consoles of the Master System (as well as the Mega Drive, AKA the Genesis) still being produced as late as 2010. Not to be intimidated however, Sega forged ahead with plans to create one of the most powerful consoles yet to be released, the 16/32-bit CPU powered Sega Genesis.

Driven on by their European successes, Sega was determined that they had a viable alternative to Nintendo’s dominance over the North American marketplace. With the release of the Genesis in the U.S. by 1989, Sega began an aggressive ad campaign as they attempted to punch a hole in Nintendo’s armor. Sega began touting the Genesis console as a more mature and risk taking device; famous slogans at the time included such memorable taglines as “The Sega Genesis does…what NintenDO’NT,” in the U.S., while more suggestive and adult oriented tag lines in their European Markets included bywords such as “The more you play with it, the harder it gets,” and “To be this good takes AGES, to be this good takes SEGA.”

Originally the Sega Genesis was packaged with a port of their popular arcade title, Altered Beast. Initially, sales were sluggish until the decision was made to repackage their consoles with their new title, Sonic the Hedgehog. This key decision, along with Sega’s decision to open a U.S.-based development team that would target the American consumer, finally began to eat away at Nintendo’s profits. Notable gaming franchises under Sega’s wing include recognizable classics Golden Axe, Ghouls ‘n Ghosts, Comix Zone, Ecco the Dolphin, Phantasy Star, and Sonic the Hedgehog who, much like what Mario had done for Nintendo, had become Sega’s official Mascot.

Mortal Kombat, Congressional Senate Hearings, and the formation of the ESRB

Early 1990’s

Sega’s persistence as the “more mature” console company verses the more family friendly approach of its competitor was about to prove that Nintendo’s policy to personally oversee and approve all titles released on their console was suddenly a very limiting thing. You see, all third party developers under Nintendo’s reach could only release a finite number of games per year, could not release a re-port of their titles to other competitors for nearly two years after and, due to Nintendo’s strict censorship policy, limited the amount of violence depicted in their games. This policy would be ultimately challenged after the very popular, but very brutal fighting game known as Mortal Kombat attempted to make its way into gamers’ living rooms.

In 1992, Midway’s flagship MK title had become a surprise smash hit in the arcades, prompting both Sega and Nintendo to vigorously pursue exclusive rights for a home port of the game. The one problem with doing so, however, was its (at the time) excessive depiction of gore, blood, and over the top violent Finishing Moves. This was something that had been previously unseen and unheard of before. Most viewed the video game landscape through Mario colored glasses; no death, no violence, no blood.

Fearing that it would violate Nintendo’s censorship policies, but still not wanting Sega to gain exclusivity to the title, Nintendo decided to heavily alter their port to depict minimal violence and gore. Some of the more cartoonish finishers remained, however the blood had been recolored into “sweat” and the more graphical content altered or removed entirely. When Sega got wind of this decision, the company decided that the time was right to strike a blow against its chief rival.

Sega released their version uncensored (at least, it was with the simple Cheat Code entered on the title screen), and outsold Nintendo’s version by a factor of four and five-to-one. This move ultimately got the attention of Nintendo’s censorship board, and closed-doors membership meetings began to vigorously debate the company’s policy on violence in the video game medium.

However, Nintendo wasn’t the only company taking a closer look at video game violence as a whole. Thanks to Mortal Kombat, the U.S. Government was now fully aware, and armed with enough evidence, to take on the video game industry’s depiction of violence in the home media.

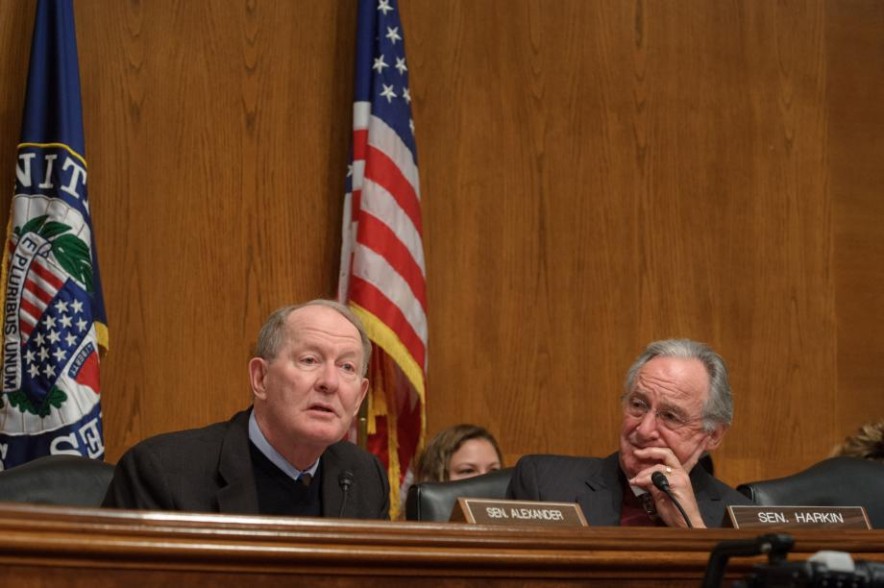

On December 9, 1993, U.S. Senators Joseph Lieberman and Herb Kohl convened a Congressional hearing to investigate the marketing of violent video game content to children. Dr. Craig A. Anderson was called into the committee to state that, “Some studies have yielded non-significant video game effects, just as some smoking studies failed to find a significant link to lung cancer. But when one combines all relevant empirical studies using meta-analytic techniques it shows that violent video games are significantly associated with: increased aggressive behavior, thoughts, and affect; increased physiological arousal; and decreased pro-social (helping) behavior.” (Dr. Anderson was later criticized in a 2005 video game court case for failing to cite research that differed from his view).

This hearing eventually led to the formations of both the Interactive Digital Software Association (IDSA) and the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) with the sole purpose of regulating and enforcing a strict code of content per rating of any and all future game titles depicting violence, sexual themes, adult language, adult situations (smoking, drinking, etc) and the depiction (or lack thereof) of blood/ gore, and/or nudity. Currently the ESRB rates any and all video games submitted to the board from Early Childhood (EC) all the way to Adults Only (AO) in most of the western markets, while several distinguished ratings boards cover most of the eastern markets, such as the PEGI (most of Europe), CERO (Japan), GRB (South Korea), ACB (Australia), and USK (German) boards, just to name a few.

Even in place, however, the battle is still ongoing on the right to control content on a governmental level. But, with the Ratings Boards now firmly in place to regulate the content of games, Nintendo’s censorship board was no longer needed. Nintendo and Sega were now allowed to distribute more mature gaming titles to the general public, with a few notable titles garnering media attention for its depiction of over the top gore (id’s Wolfenstein and Doom), and highly-sexualized themes (Digital Picture’s Night Trap).

For the rest of 1993 and the majority of 1994, Sega and Nintendo would remain the top two companies in America, having beaten most, if not all of, their major competitors, as well as weathering through a Congressional hearing that could have upended both companies prematurely. It wasn’t until December of 1994 that a ghost from Nintendo’s past would come back to haunt it.

And completely reshape the way people played video games for the foreseeable future.

To Be Continued in Chapter II…

![[PROTOTYPE]](http://www.enthusiacs.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/title-104x104.jpg)

God I feel old reading this – good read, but sobering 🙂

Good ol’ Mortal Kombat. Fighting ever onwards.